In memory of Nathaniel Thompson, on the 235th anniversary of his death

(May 29, 1726 – June 25, 1785)

The People of the Dawnland: The Abenaki

The house on Thompson’s Farm stands on lands (N’dakinna) originally occupied by the Abenaki / Abénaquis (People of the Dawnland) of the Wabanaki Confederacy (Dawnland Confederacy). Yet, as blogger Janice Brown has observed, “By the mid-1700s, 90% of the original native inhabitants were no longer in New Hampshire. Many died from European host-delivered diseases and wars, some were enslaved, and some moved on to other places. Still others ‘disappeared’ by marrying into local non-native families. By the time of the American Revolution, less than 1,000 Abenaki remained.” Or at least in ways that were visible to outsiders.

Devon descends from the Abenaki on his mother’s side.

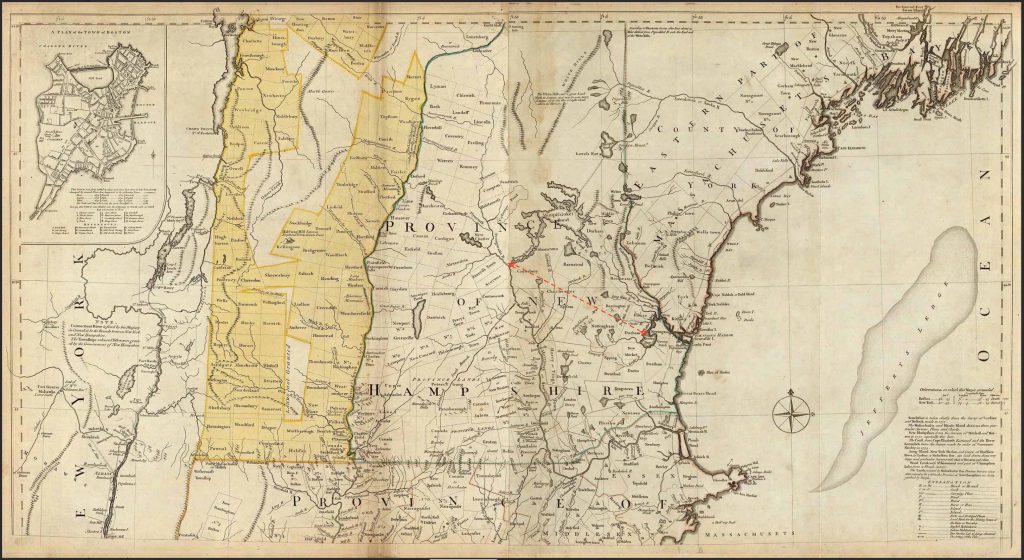

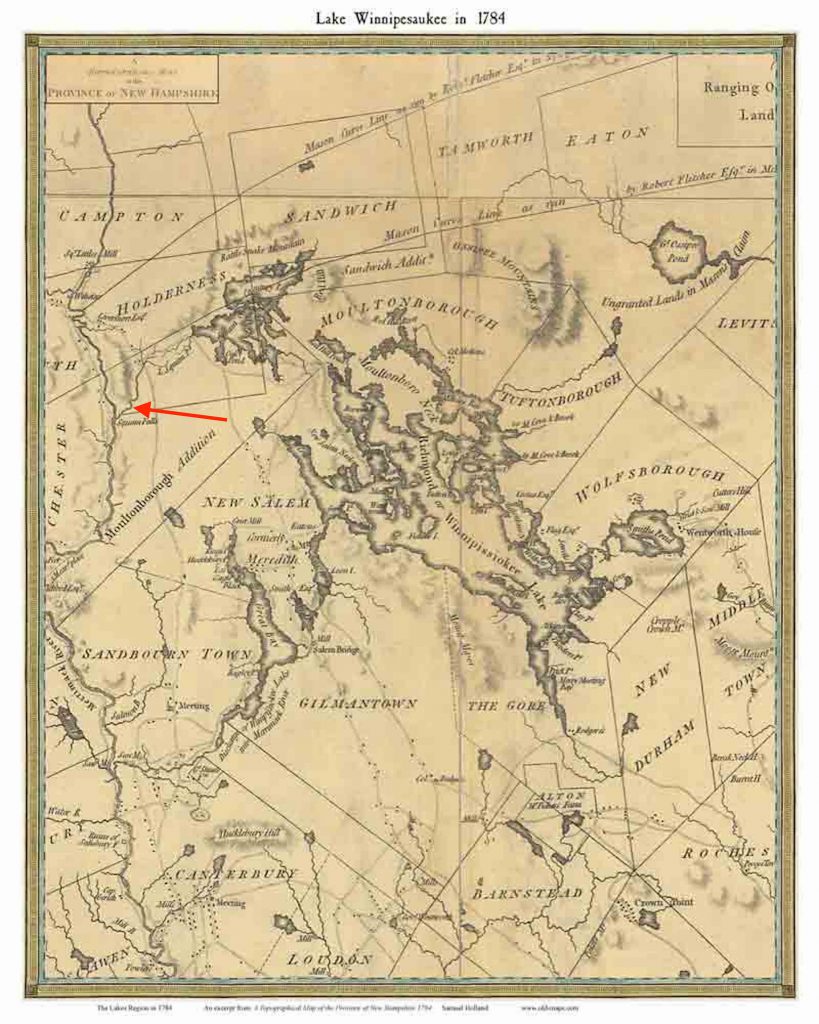

The Squam Lakes, lying in the center of what would become New Hampshire, were part of a trade route for the Abenaki people, leading to the Squam, Pemigewasset, and Merrimack Rivers, and the Atlantic coast. Indigenous narratives about the Lakes Region reorient “the viewer’s perspective to see the land from the water, rather than the water from the land.”

The Indigenous NH Collaborative Collective has created a Land Recognition Statement that we embrace. Accordingly, we understand our own work to be located on “N’dakinna, which is the traditional ancestral homeland of the Abenaki, Pennacook and Wabanaki Peoples past and present. We acknowledge and honor with gratitude the land and waterways and the alnobak (people) who have stewarded N’dakinna throughout the generations.”

The Coming of Nathaniel Thompson

The 1886 Gazetteer of Grafton County, N.H. narrates the story of how Nathaniel Thompson came to hold this land:

Among the pioneers, who aided in the settlement of the town of Holderness, which included the present town of Ashland, was Nathaniel Thompson, who removed from Durham to Holderness, between October, 1770, and August, 1771.

He was baptized an “infant” by the Rev. Hugh Adams of Oyster River, May 29, 1726, and married Elizabeth Stevens of Durham as early as 1761. He was an active, enterprising man, and, in the various conveyances of land, he is called ”trader,” ”shipwright,” and ”gentleman.” As early as 1753, he sold land in Durham for £2,000, probably to furnish capital to go into trade.

He was a highway surveyor in Durham in 1766. In 1768 he was surveyor of highway and sealer of leather, in 1769 he was sealer of leather; and the same year, “Ensign Nathaniel Thompson” and Ebenezer Thompson, afterwards judge, were of the committee of six to receive and dispose of the proportion of school money for the districts to which they respectively belonged. He gave a deed, October 16, 1770, as “Nathaniel Thompson of Durham, province of N. H., gentleman,” of the dwelling house and land on the Mast Road, where he lived. It was shortly after this date that he removed to New Holderness, for his tax in Durham is abated February 11, 1771, and his name appears no more in the town records.

August 24, 1771, “Nathaniel Thompson of New Holderness” conveys land in Pembroke, which he had bought of his brother Benjamin.

He had been offered a large tract of land by the proprietors of Holderness if he “would build and run a gristmill and sawmill in that town, and thus aid in the development of that section.”

It was common for early New England mills to handle both grain and wood. They were also the precursors of the 19th-century textile mills.

Upon the outlet of Lake Asquam [now known as Little Squam Lake], Nathaniel Thompson built his mills, and upon its banks he made his home, and planted his orchards. Here he settled with his wife and five children, and five more children were born after they had located in Holderness. Polly, the sixth child, was born February 6, 1772; married John Hill of Durham, her second cousin, February 4, 1796; removed to Danville, Vt., thence in 1816, to Ogden, N.Y., where she died December 17, 1843.

She was never weary of recounting to her daughters the poetry and tragedy of her youthful life at Holderness. When she was about thirteen and her youngest brother about two years of age, their brave, strong father was sent for by his old neighbors to inspect a ship built at the Durham shipyards.

To get from Holderness to Durham would have been a good journey by horseback (it being safe to assume that Nathaniel probably did not travel in a straight line).

He took the horseback journey through the wilderness to the coast, pronounced the ship seaworthy, and it was slipping into the waters from the dock when one of the skids broke and flew with great force, striking the leg of Nathaniel Thompson and producing a severe compound fracture. This caused his death, four days later, at the house of a friend nearby, and he was buried among his ancestors and near relatives in Durham. It was in 1785, three years after the close of the Revolutionary war, and public conveyances and mails between the coast and the interior of New Hampshire were practically unknown.” (A Great Mother.)

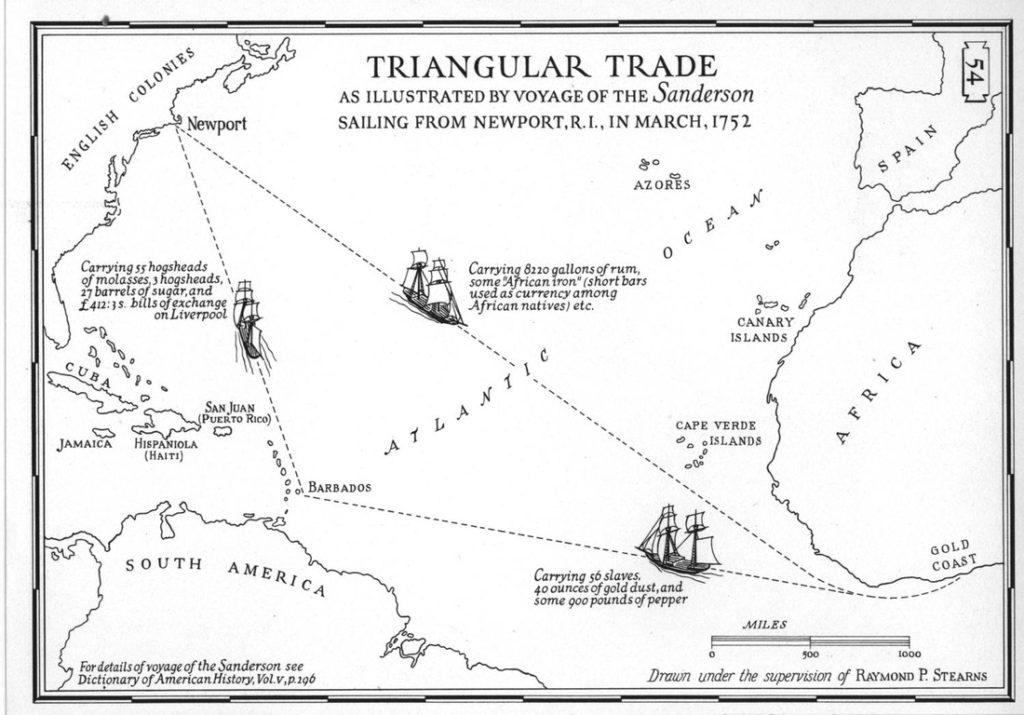

James Thompson was master of the sloop Nancy in 1752, and his brother, Nathaniel, shipped goods in it from Barbadoes, April 11, 1752, consigned to Benjamin Matthews, Jonathan Thompson, Jr., & Co., of Piscataqua.

Here’s where things get complicated. Eighteenth-century trade between New England and Barbados was part of a network that included the British colonies, the islands of the Caribbean, West Africa, and England:

Trade with the colonies in North America was an important market for British manufactured goods while, in turn, the New England economy evolved so that these purchases of British manufactured products were financed by the trade with the West Indies. It is common to talk of the Slave ‘Triangular Trade’ involving Old England and the Caribbean. However, it is probably more accurate to talk of the ‘Triangular Trades’, plural, as an important triangle went from New England to West Africa with rum, which could be traded for captives in Africa. These slaves could be exchanged for molasses in the West Indies to supply the rum distilling industry in New England.

Mayflower Myths. New England colonies and the British Caribbean slave colonies. Posted July 3, 2019.

This suggests that before Nathaniel relocated from Durham to Holderness, he and his brother James were part of one such triangular trade. Their involvement illustrates how the influence of that trade extended into New Hampshire. Although not slaveholders themselves, Nathaniel’s and James’s commercial ventures played a part in supporting the West Indian slave economy during the mid-eighteenth century.

Nathaniel Thompson was the son of John3, John2, William1, of Dover, as early as 1647, and was a cousin of Judge Ebenezer Thompson of Revolutionary fame. He was a selectman in Holderness in 1773, and in 1776 Nathaniel Thompson and four others signed a petition for ammunition and arms, as being in danger of attack from Canada.

Rev. Curtis Coe, then the pastor at Durham, made the following entry in his record of burial in the parish: “1785, June 25. Was buried, Mr. Nathaniel Thompson of New Holderness who died in this town.”

(Child, Hamilton, comp. and pub. 1886. The New Hampshire Gazetteer of Grafton County, N.H.: 1709-1886, Part First. Syracuse, N.Y.: The Syracuse Journal Company, pp. 148-150.)

Descendants of Nathaniel Thompson continued to live on the land, which lay along the Squam River, building the current house in 1834. Nathaniel’s wife Elizabeth is buried in the Thompson Street Cemetery, which borders our land down near the river. A historic easement allows “the right to pass and repass to land from Thompson graveyard”.

Resources

Abenaki Couple, an 18th-century watercolor by an unknown artist. Courtesy of the City of Montreal Records Management & Archives, Montreal, Canada.

Brown, Janice. 2006. New Hampshire’s Native Americans: Hiding in Plain Sight. https://www.cowhampshireblog.com/2006/08/10/new-hampshires-native-americans-hiding-in-plain-sight/. (See also https://web.archive.org/web/20160624011623/http://www.tolatsga.org/aben.html)

For Abenaki names of the region now known as Grafton County, see: Cowass North America Inc. N’dakina – Our Homelands & People. http://www.cowasuck.org/history/ndakina.html.

For more information about the Land Acknowledgement Statement, see https://indigenousnh.com/land-acknowledgement/.

To learn about the indigenous history of the land you live on: https://www.yesmagazine.org/issue/decolonize/2018/04/16/this-app-can-tell-you-the-indigenous-history-of-the-land-you-live-on/

If you’re interested in early New England mills, check out Edward Peirce Hamilton’s “The New England Village Mill“.

For more on the work of the colonial surveyors: http://www.colonialsurveyor.com/life-of-a-1700s-surveyor/

LAURA WHITEHOUSE

What a wonderful post Linda! So very interesting…I just LOVE the fact that Devon descends from the Abanaki! This is a really lovely part of your shared history and a beautiful way to honor this land! I am excited to follow this journey with you so thank you for taking the time to share with those who care about you. I wish you both so many wonderful experiences and great peace and joy in your new home!!!

Linda Barnes

Wonderful to see you here, Laura, and thank you for the kind words!

Lance Laird

Linda, this is a great story. I would imagine that the local historical society is going to find you out soon!

Linda Barnes

Thanks, Lance—and as I learn about the next generations, it only gets more interesting!