This is a story of removing one chimney and restoring another.

It was the best of times,

it was the worst of times,

it was the age of wisdom,

it was the age of foolishness,

it was the epoch of belief,

it was the epoch of incredulity,

it was the season of Light,

it was the season of Darkness,

it was the spring of hope,

it was the winter of despair,

we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way— in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.

Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities, Book the First, Chapter I, page 1

I told Devon emphatically that, even with a title like “A Tale of Two Chimneys”, there was no way I’d start out with the frequently quoted passage from Charles Dickens—until I reread it, and saw how close to our current truth it comes. Even more so, having just finished Heather Cox Richardson’s September 12th entry for her daily Letters from an American. She observes:

I write a lot about the philosophy of living in a fact-based reality, explaining the Enlightenment idea that we can move society forward only by evaluating fact-based arguments. Replacing facts with fiction means that as a society we cannot accurately evaluate new information, and then shape policy according to solid evidence. But the Trump administration’s attempt to hide reality under their own narrative reveals a more immediate injury. You cannot make good decisions about your life or your future if someone keeps you in the dark about what is really going on, any more than you can make good business decisions if your partner is secretly cooking the books.

Heather Cox Richardson. “Letter from an American”. September 12, 2020

Knowledge truly is power.

We live in a time when our “noisiest authorities” insist on “superlative degrees of comparison only”—”the best”, “the worst”, “the greatest”, “the strongest”, “the most” or, for that matter, “the least racist”. Richardson’s words, together with those of Dickens, remind me that as Devon and I have brought our decisions about this renovation to fruition, we have been acutely aware of how climate change, the COVID-19 pandemic, and our country’s history of racial violence have converged with deadly effect.

Researchers like Merrill Singer and Bayla Ostrach have studied what happens when different assaults on public health and well-being coincide. When these conditions do not just coexist as parallel, disconnected catastrophes, they can become “intertwined and cumulative.” Each problem intensifies and exacerbates the effects of the others, making the outcome for each one even worse than it might have been separately.

These clusters of interactions represent what Singer has called a “syndemic”—a “synergistic epidemic”.

Our renovation does not take place in a cultural or historical vacuum. Our choices around energy conservation, for example, differ markedly from those made in 1834 by John Hayes Thompson, the house’s original builder, precisely because of this context in which we are working.

Our hope to protect and nurture native plants, pollinators, birds, and other wildlife stems from that same context, as does our commitment to create a haven to which we, our families, friends, and colleagues, can retreat to regroup and go back out to work for change.

But for the moment, I go back to chimneys.

Of Chimneys

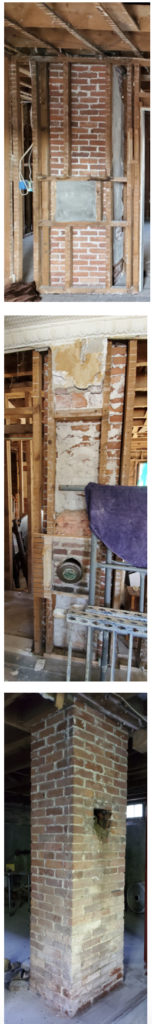

The house started out with two of them—one in the kitchen, the other standing between the dining and living rooms. Both extended from the basement up through the roof. Given their locations, it was clear they had been part of the original house.

Chimneys, like everything, have a history. In Europe, prior to their development, people often constructed a brick or stone platform upon which they built a fire in the center of a room. A hole in the roof overhead allowed at least some smoke to exit.

Orville Butler explains that, although we do not know the exact origin of chimneys, they seem to date back to around the twelfth century.

By the eighteenth century, English courts required the use of brick to reduce the hazard of unintended fires—although early American colonists without access to bricks still resorted to wooden chimneys lined with clay.

The Making of Bricks

When I told Devon that I planned to write about making bricks, he commented that his only previous exposure to the topic had been through the 1956 movie The Ten Commandments.

Early British colonists regularly imagined their endeavors in biblical terms, but I doubt they had Moses in mind when making their own bricks—even though the methods seem not to have changed all that much. (Filmed on location in Egypt, with thousands of local extras, I can’t help wonder whether the casting director found an actual Egyptian brick maker!)

Within short order, the New England colonists began to fashion their own bricks. For example, a group of 350 led by Puritan minister Francis Higginson, arrived in Salem, Massachusetts on June 29, 1629. Within a month of their arrival, Higginson wrote, “Here is good clay to make Bricke and Tyles and Earthen pots, as need to be. At this instant we are setting a brick kiln on worke to make Brickes and Tyles for the building of our houses.” By the eighteenth century, local brick works had become far more common.

Despite variations throughout the colonies, there were also predictable commonalities in the actual making of bricks. (The process did not change significantly until 1852, when Richard VerValen invented a steam-powered machine to shape them.)

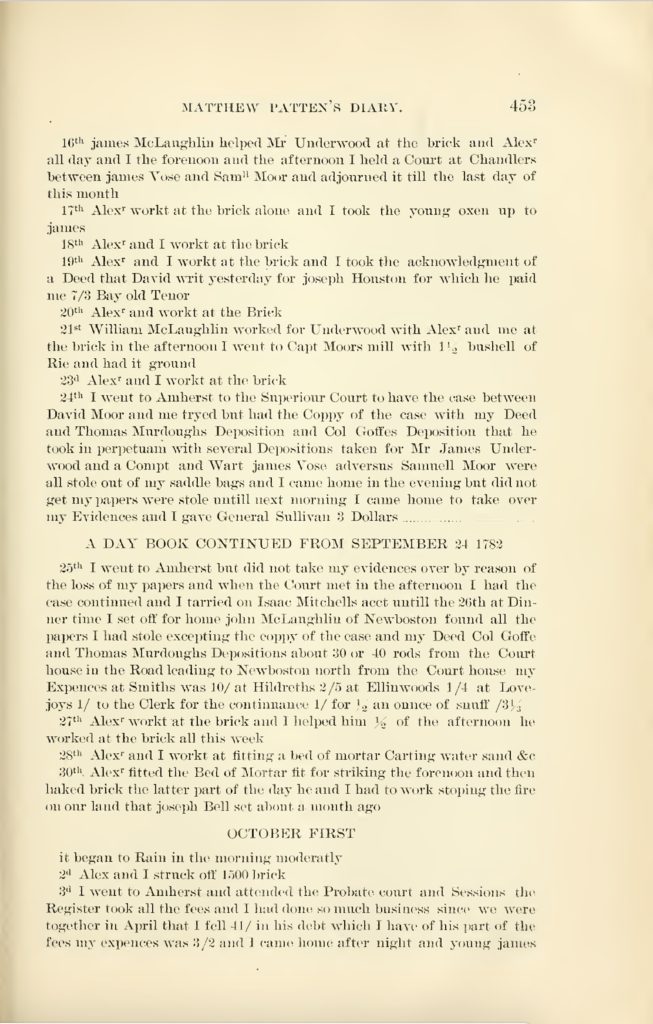

Matthew Patten’s Day Book

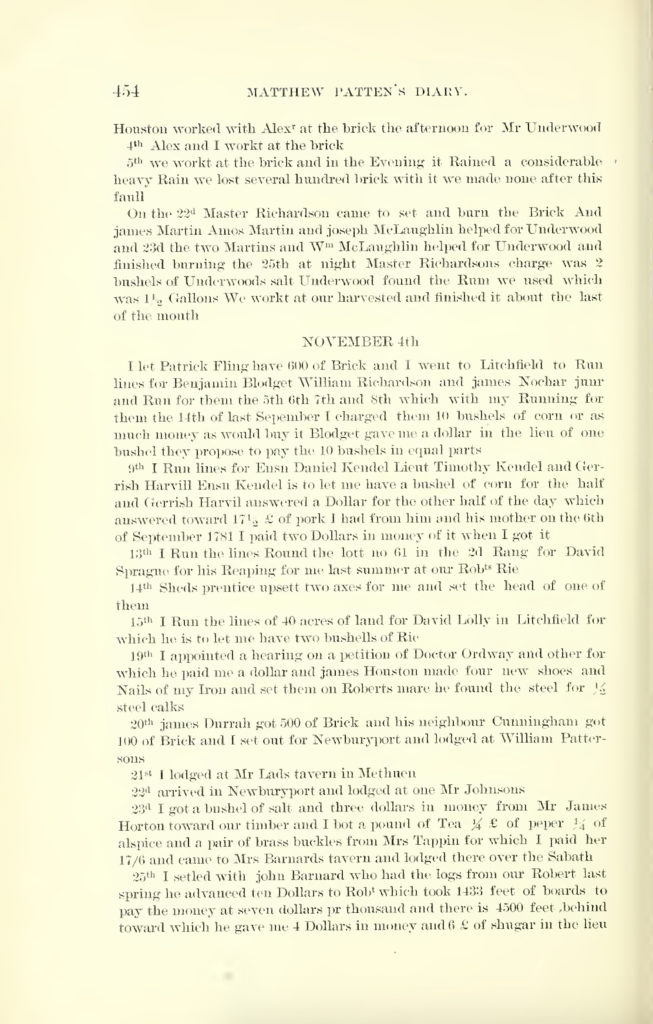

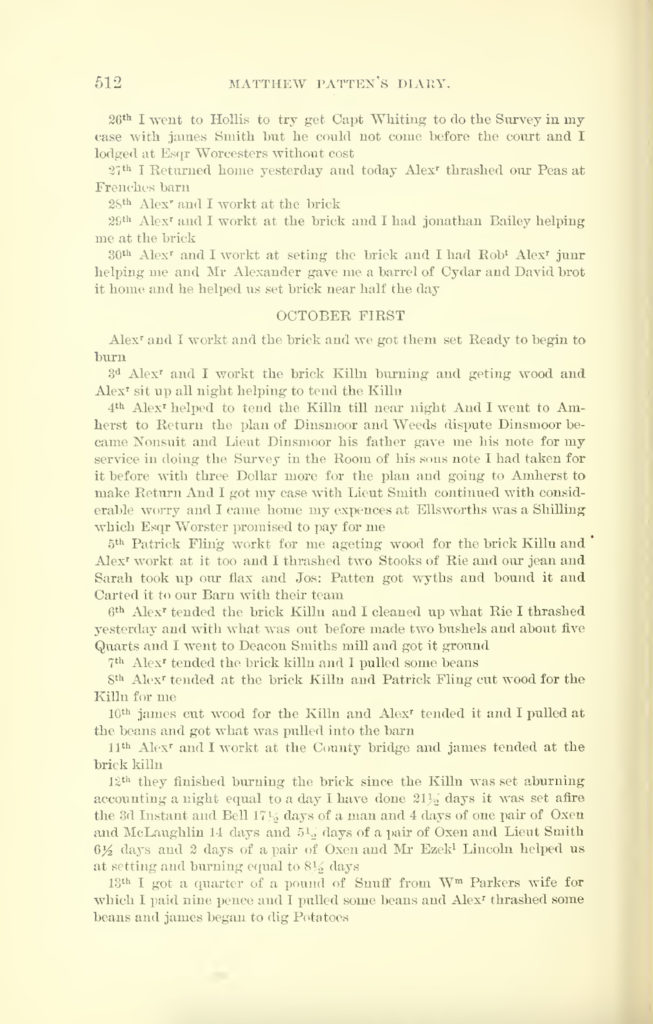

Judge and Justice of the Peace Matthew Patten (May 19, 1719 – August 27, 1795), an Irish immigrant who came to the British colonies with his family in 1728 at nine, would go on to live in Bedford, New Hampshire as an adult. He kept journals throughout his life, in which he entered prosaic notes about his daily activities—his work in the court, farm tasks, travel, and exchanges with his family, neighbors, and colleagues.

In 1782, he described his experience of molding bricks with his son Alexander (pages 452-454); in 1784, he detailed their firing bricks in a kiln (p.512).

The following videos demonstrate the procedures described by Patten. The first focuses on the molding of bricks. The second demonstrates their firing.

Nineteenth-Century Brickmaking in New Hampshire

By 1834 in New Hampshire, even when a region had the right kind of clay to make bricks, the major obstacle to expanding production was the lack of transport for such heavy loads. I doubt, for example, that John Hayes Thompson went down to Hooksett—a growing center of brickmaking—to haul back enough stock to build two chimneys and the foundation that rested on top of the field stones.

from Basement

to Second-Floor Bedrooms

It would have required a journey of at least fifty miles, and vehicles of the day would have been hard pressed to carry that much weight over such a great distance on unfinished roadways. (Records of early town meetings included regular discussions of who would clear different stretches of land to lay new roads and expand the transportation network.)

Until the train lines came through—which, in Holderness (later Ashland) did not happen until 1849—brick making was usually a local undertaking, often limited to supplying bricks for chimneys.

New Hampshire historian James Garvin notes that those building the house might themselves take part in the work, only bringing in someone with more expertise (as Matthew Patten did with “Master Richardson”) when it came time to stack the bricks, build the kiln, and oversee the firing itself. And, like Patten, an individual who gained some experience might also eventually undertake those tasks.

I don’t know for certain where John Hayes got his bricks, or whether he had a hand in making them. However, given local clay pits and accounts like Patten’s, I speculate that he did.

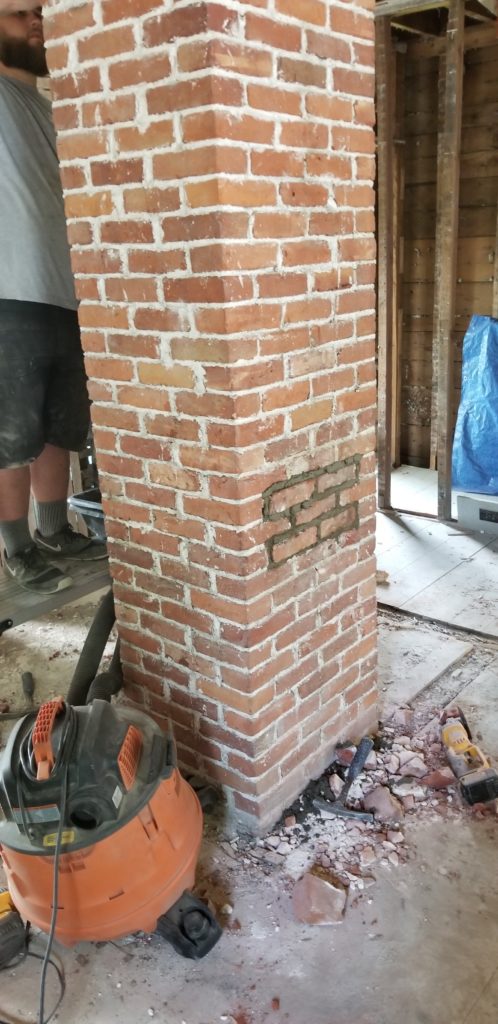

The bricks in our house are red, a color that many people assume is standard. However, the color depends on the composition of the clay. A higher iron content, for example, can result in a redder result.

During the Industrial Age in early nineteenth-century England, London builders chose red bricks to ensure that coach and cab drivers could see them through the city’s dense fog and avoid accidents.

Enter the Cast-Iron Stove

Even when it became common to use bricks in chimney-making, two problems persisted. The first involved how to channel smoke up and out of a dwelling. The second was that the fireplaces set into these chimneys did not distribute heat effectively throughout a room.

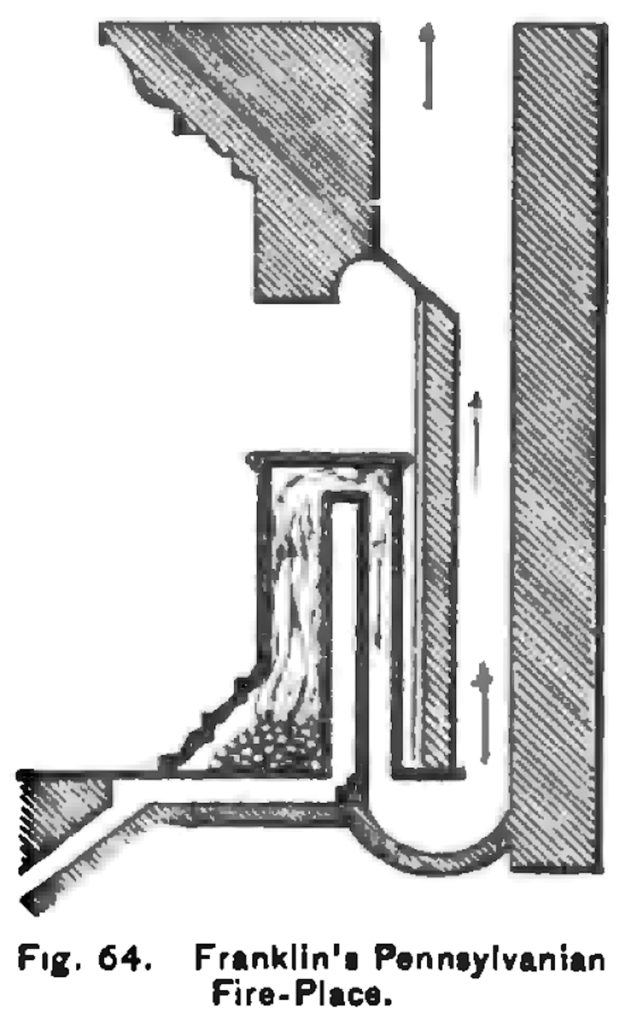

Eighteenth-century inventors like Benjamin Franklin and Benjamin Thompson (not related) of Woburn, Massachusetts attempted to solve the problem by redesigning the internal structure of chimneys and designing attached stoves to direct smoke outside and heat rooms more efficiently. (Thompson, a British loyalist, later returned to Europe where, in Bavaria, he received the title of Count Rumford.)

However, as Putnam goes on to observe, “The chief difficulty with all these arrangements having the reversed draught is their liability to smoke, and to clog with soot.”

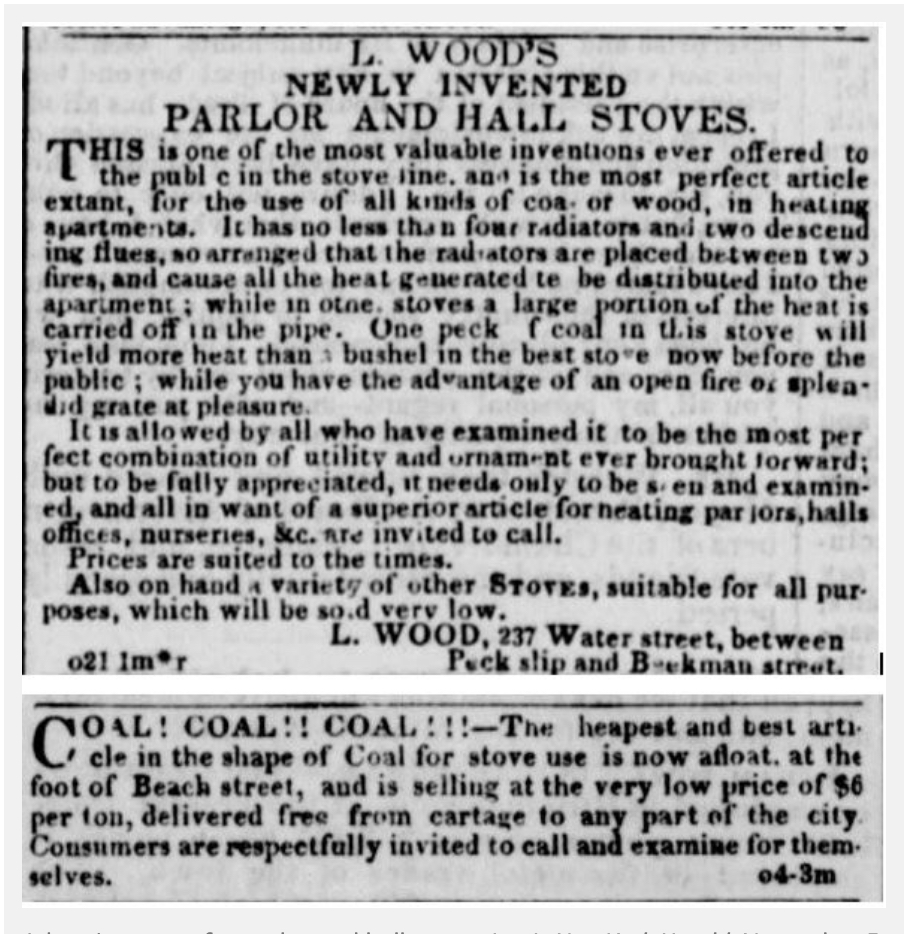

In the nineteenth century, as coal became a favored fuel it, too, posed the problem of gritty smoke and soot. One solution emerged in wood- and coal-burning cast-iron stoves. These stoves connected to a chimney through a pipe. The stove served the dual purpose of drawing off the smoke, warming the room, and sometimes also providing a cooking surface.

Vendors were quick to advertise the stoves themselves, emphasizing that customers could use them to burn either wood or coal.

Not everyone was a fan of coal, which dried out the air. Historian Margaret Highland cites “The Haunted Adjutant” in Graham’s Monthly Magazine (1845): “If flesh be indeed grass, anthracite [i.e., coal] will soon desiccate the American public into a very creditable hortus siccus [collection of dried plants].”

Nonetheless, growing shortages of firewood led to coal becoming its substitute.

Between 1650 and 1850, settlers managed to cut down half of the Northeast’s forest cover and remove most non-forest timber. This only increased as the United States industrialized. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, wood use for fuel spiked around 1870, providing 90 percent of railroad fuel. At its peak, the per capital consumption of firewood was a whopping 4.5 cords per capita. (One cord of firewood is four feet high by four feet wide by eight feet long.)

Late in the 19th century, though, coal became the fuel of choice. But by then, it was too late for America’s forests.

Erin Blakemore (2018)

Neither of our chimneys had fireplaces. Instead, the one in the kitchen had a single “thimble”—a round opening through which the stovepipe connected to the flue inside the chimney, carrying the smoke outside. The second chimney had three thimbles on the first floor, and two on the second.

Of Furnaces and Heating Oil

As some of the pictures above show, someone had plugged up all the chimney thimbles, probably when a former owner added a furnace that burned heating oil. As the Rush Locates group explains, “In the early 1920’s, with the invention of electric fans, the idea of a ‘forced air’ furnace became a reality. Diesel fuel was being utilized in engines by 1900. Its prevalence led to using it as a heat source alongside wood, sawdust, oil, (rarely) coal, and natural gas burners.”

I suspect it may have been Marsena Blake who installed the oil furnace. He owned the house from 1888 until his death in 1948, and seems to have been a fan of new technologies. (Town records show that he owned an automobile as early as 1904).

Subsequent owners continued to use heating oil. Indeed, although use of oil furnaces had started to taper off by the 1960s, the U.S. Energy Information Administration notes that even by 2018, “about 5.5 million households in the United States used heating oil (distillate fuel oil) as their main space heating fuel, and about 82% of those households were in the U.S. Northeast.”

When we began our planning, little did we know that adding wood stoves would restore the original function of the chimneys, and result in the way things used to look! With the geothermal system, we won’t need as many of them, but here are the two we will install.

Jøtul F3 CB Wood Stove

Jøtul F602 Wood Stove

Demolitions

When we began work on the house, not only were the thimbles plugged; framing still encased both chimneys. Devon had to remove it, so the crew from Lakes Region Chimney Pro could take out the kitchen chimney and repair the one in the living-room.

Here is what happened with the chimney originally in the kitchen:

Here you can see the repair and rebuilding of the main chimney.

And here is how things ended up.

Resources

Dickens, Charles. A Tale of Two Cities: A Story of the French Revolution. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/98/98-h/98-h.htm.

Richardson, Heather Cox. Letters from an American. https://heathercoxrichardson.substack.com/.

For more on syndemics, you can check out a special 2017 issue of Lancet https://www.thelancet.com/series/syndemics.

For information about Merrill Singer, see: https://chip.uconn.edu/person/merrill-singer-phd/

To learn more about the work of Bayla Ostrach, see: https://www.bumc.bu.edu/gms/maccp/faculty/bayla-ostrach/

Orville Butler provides a concise overview of how residential chimneys developed, in “Smoke Gets in Your Eye: The Development of the House Chimney.” https://ultimatehistoryproject.com/chimneys.html.

Buckley, Jim. Rumford: The Fireplace That’s More Like It Used to Be than Ever Before. Buckley Rumford Company. http://www.rumford.com/articleRumford.html.

The Ten Commandments. Directed by Cecil B. DeMille, performances by Charlton Heston, Yul Brynner, Anne Baxter, Edward G. Robinson, and Yvonne De Carlo, Paramount Pictures, 1956.

For a detailed description of the brick-making process, see: Van Wagner. 2009. Winning, Dashing, and Firing: Making Bricks in Danville PA. http://vanwagnermusic.com/danvillebricks.htm.

James L. Garvin focuses on the history of brickmaking in New Hampshire. See Garvin, James L. 1994. Small-Scale Brickmaking in New Hampshire. The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archeology 20(1/2): 19-31. http://www.james-garvin.com/reports.html.

If you’re still interested in learning more, check out:

Patten, Matthew. 1903. The Diary of Matthew Patten of Bedford, N.H. Concord, N.H.: Rumford Printing Company. https://archive.org/details/diaryofmatthewpa00patt

Ewan, Nat. 1970. Early Brickmaking in the Colonies. West Jersey History Project. http://www.westjerseyhistory.org/articles/brickmaking/

Fillick, Sarah K., and Tamara Gaskell. Brickmaking and Brickmakers. Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/brickmaking-and-brickmakers/

Spain, James W. 2020. Making bricks for city’s houses. Concord Monitor, May 6. https://www.concordmonitor.com/vintage-34124804.

For practices related to currency in the British colonies, see Michener, Ron. 2003. Money in the American Colonies. EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples. Revised January 13, 2011. http://eh.net/encyclopedia/money-in-the-american-colonies/.

In 1881, John Pickering Putnam published a detailed history of fireplaces, their designs, and innovators in The Open Fire-place in All Ages. It provides an account of the Franklin stove and others.

For more on coal-burning cast-iron stoves, see Highland, Margaret. 2018. Cheerful and Bright (and Smoky): Staying Warm in 19th-Century American Homes. https://mansionmusings.wordpress.com/2018/11/15/cheerful-and-bright-and-smoky-staying-warm-in-19th-century-american-homes/.

For some background on firewood shortages in the nineteenth century, see Blakemore, Erin. 2018. The Firewood Shortage That Helped Give Birth to America. https://www.history.com/news/the-firewood-shortage-that-helped-give-birth-to-america

For more information about chimney thimbles, see Jagg Xaxx. Masonry Chimney Thimble Installation. https://www.ehow.com/how_12193807_masonry-chimney-thimble-installation.html.

For background on the use of diesel fuel to heat homes, see Rush Locates, LLC. The History of Diesel Oil Heating in Homes. https://www.rushlocates.com/history-diesel-oil-heating-homes/

U.S. Energy Information Administration. Heating Oil Explained. https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/heating-oil/use-of-heating-oil.php

Deb

The amount of research is amazing. Great videos. I enjoy the old adds. And of course, this is a great amount of work. You are truly fixing the house from the inside out. Thanks for giving this deserving, old house new life.

Linda Barnes

Thanks, Deb!