“Ogni blocco di pietra ha una statua dentro di sé ed è compito dello scultore scoprirla.” (Every block of stone has a statue inside it and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it.)

– Michelangelo

Michael Agnelli, the owner prior to Prentice Hammond, Jr., had been unable to keep up with things. He had lost his job, and his circumstances had grown so difficult that he could no longer support the mortgage. The house went into foreclosure. On December 19, 2006, the bank sold it at auction to a Matt Dupee, who signed it over to Freeride Investment Partners.

On January 12, 2007, Michael’s friend Prentice bought the house from Freeride. Michael would rent it from him, while getting back on his feet, and then buy Prentice out.

Neither could have anticipated that Michael would develop cancer and die on April 28, 2009 at the age of fifty-one. The house was one-hundred-and-seventy-five.

The Befores

Not having planned to keep the house long-term or to live there, Prentice now had to decide what to do with it. Sell it as it was? Repair and sell it? Restore it and live there after all? Ashland sits virtually at the center of New Hampshire; most of his family lived on the Vermont border—too far away to make the town a realistic retirement location.

As he took stock of how things stood, he could see how badly the house’s interior had deteriorated. Paint had cracked and peeled. Water leaks had damaged the ceilings, plaster, and aging wallpaper.

Stains and age had worn away the finish on the floors.

In the basement, the floors were bare dirt. Mortar between foundation stones had crumbled and fallen away.

Pipes had rusted, as had the old oil tank. Insulation was falling down.

Prentice felt a strong sense of responsibility for the house. He didn’t want it to keep deteriorating, and wanted even less to sell it if it was unsafe. One of his brothers offered to help with repairs, and even drew up plans in case Prentice did decide to renovate.

Regardless of his ultimate decision, Prentice could see that, in the short run, he would have to gut the house for renovation even to be possible.

Then what would the statue in the stone look like?

The Gutting

After Michael’s death in 2009, one of Prentice’s first steps involved bringing in a roofer to repair the high side on the left of the barn to prevent further damage from leaks. In 2011, Prentice and his brother worked on repairing the roof on the low side of the barn.

In August of 2012, Prentice and Deb met. When he showed her the house, she recognized its beauty and potential. There was only one hitch. Neither had family in the area and so didn’t want to live there (or even use the house as a second property) at that point in their lives.

Nevertheless, given Deb’s enthusiasm for the house and Prentice’s desire to see it restored, she threw herself into the project almost immediately. “I think in the first month we knew each other,” she said, “I was hauling half-bundles of shingles at a time up the scaffolding.”

At that point, the house had a front porch. The style of its decorative elements dated back to the nineteenth century. Driving around the area, you still see them on older farmhouses.

To repair the road side of the connector roof and the adjoining barn roof to that height, Prentice and his brother removed the porch. It had rotted along where it joined the house, but Deb carefully saved and preserved the decorative pieces.

Prentice and she thought maybe the next owner might re-use these parts to build a another porch—one that would be wider, deeper, and more centered. (Of the old one, Prentice said, “That thing was so narrow, you could sit in a chair out there, and nobody could get by you.”)

Together, they envisioned the many directions a renovation could take—vaulting the ceiling over the connecting unit and converting it into a master bedroom suite overlooking the pond; vaulting a section of the roof in the original master bedroom for a southern exposure and a view over the road; opening up the ceiling over the smallest bedroom on the second floor, or even the whole north end, to make room for a bathroom and closets for the master bedroom. They deliberated over any number of potential kitchen designs, and whether to move the front door, or the kitchen door.

They took pleasure in imagining endless possible layouts—albeit ones they would never build for themselves. Instead, they hoped to find a buyer who would not only apply their own creativity and original design to the clean canvas the two of them had prepared, but would also then enjoy living there.

Still, whoever ended up with what they referred to as their “diamond in the rough,” they still had to gut the interior of the house. Otherwise, it would slide further into what Deb called, “the sorry fate of continued neglect.”

The task was daunting, but they began work in 2013.

All That Horsehair Plaster

The walls had originally been finished with wood lath and horsehair plaster, commonly used up through World War II. However, the post-war expansion of the construction industry required materials that dried fast and didn’t entail the same levels of skill to apply. Horsehair plaster—a labor-intensive method—involved spreading on three different coats of material to create the smooth final surface.

First, thin strips of lath were nailed to the framework. The first, or scratch, coat of plaster, usually a mixture of lime, gypsum, sand and, sometimes, horsehair, was then troweled on to the lath. This “keyed” [it] to the lath. It penetrated the slots between the lath and hardened to form a bond. But before it was completely dry the plasterer scratched it with a sharp stick or metal scratcher to help the second [brown] coat bond. That coat, applied after the scratch coat had dried, was made of gypsum and sand.

After the brown [second] coat had dried, a third and final coat was applied. That was a lime-gypsum mixture that produced a smooth, hard surface.

Edward R. Lipinski, “History is Plastered with Plaster

Why horsehair? The length and strength of hair from a horse’s mane and tail added to the plaster’s structural durability.

As construction expert Mike Bailey explains, the pieces of hair were about six inches long, and had to be thoroughly mixed in to avoid tangles and lumps. It is easy to assume nowadays that more modern techniques are superior. But horsehair plaster’s density often made it more soundproof, fire safe, flexible, and better insulated.

Removing the plaster, however, is a stinker of a job. You have to pry it from the surface and from the spaces between the laths. The laths themselves then have to be crow-barred off the studs. You end up with piles of lath strips—most still riddled with nails you have to remove for safe disposal of the wood—and chunks of plaster.

And free-floating dust. Always the dust.

Layer after layer after layer had to be stripped away. Deb poured endless sweat equity into the job, not only locating and coordinating subcontractors for specific projects, but also tackling the many grubbier hands-on tasks herself.

“I was there pulling nails,” she recalled, “ripping stuff out and throwing it out the second-floor window, hoping it would hit the dumpsters below. I think my rear has permanent indentations from all those hours of sitting on a milk crate to pull plaster off the walls and nails out of boards!”

But there was more.

Prentice and she tore out all the old plumbing, along with an old porcelain sink and drainboard in the kitchen. The metal cabinetry underneath had rusted through, and there was a rotted depression in the floor.

Deb later recalled, “At one point some critter jumped out and scared the bejeebers out of me when I pulled the cabinet from under there!”

A group of handymen who had worked with her on other projects in Rhode Island came up to remove the asphalt shingles from the back of the barn. They also provided extensive assistance in gutting the house.

Deb pulled aluminum siding from the north wall of the house to check the condition of the wooden clapboards underneath. Local carpenter Dean Marcroft and his crew delineated a separation point between the barn and the house. They then cleaned up and repaired the clapboards where the porch had been removed, and restored areas in the frame that had rotted.

When all was said and done—except for a few clapboards that needed to be replaced—most of them still looked good.

The Outcome

Having taken out the plaster and laths, now the framing and walls throughout the house stood in the open. The basement had a new cement floor and walls, and part of the barn and house had a new roof. The place was ready for the installation of new plumbing. Although it would need eventual rewiring, it still had functioning electricity.

By the time Prentice and Deb decided they had done enough, they had finished virtually everything necessary for someone else to step in. Had they continued, they would have begun an actual renovation themselves and, as Deb put it, “Infringed on what an eventual buyer might want to do.”

It had been a staggering amount of work. The contours of the statue had emerged from the stone.

The Barn

This is how Devon and I first saw the house on September 28, 2019. We entered through the barn, wondering how well it might serve as a potential cabinet shop for Devon.

Notice all that Prentice’s brother did to replace wood that had rotted. He used rough sawn boards from Sharps Lumber to install new beams, as well as adding studs to the wall on the left. (Prentice later told me he wished he had known about Sharps back in 2009, as he would have had the roofer use rough sawn lumber when working on the barn).

The main floor might have been somewhat uneven, but it was solid. At one point, we learned, an owner had used the barn as their garage, parking multiple cars in it (we are still not sure which owner this was). It would hold the weight of Devon’s equipment.

The stairs at the far end of this level led up to a second floor, and also down to old horse stalls below.

Here, in the upper floor, Prentice’s brother replaced the third of the older wood flooring closer to the back of the barn (closest to you in the picture); Dean Marcroft and his crew replaced the other two-thirds, extending to the front.

You can also see the barn’s post and beam construction. Post and beam structures use metal fasteners—in this case, nails and connectors—the rods running vertically from the ceiling to the floor, and diagonally from the side walls outward to anchor into the floor. The rods worked with the truss system of crossbeams overhead to support the floor as a whole.

The square white door at the far end looks out over the street side, and was once used to haul up bales of hay for winter storage.

Note the hole in the left-hand wall (below). A little ways before it, a chute in the floor (covered by a piece of plywood) allowed the farmer to drop bales of hay all the way down to the basement of the barn for the horses and livestock.

The hole in the wall opened into an addition that connected the barn to the original house. Here is what you would have seen if you looked through it.

The wall covered with clapboards had been the exterior of the house prior to the addition of the connector. Through the hole in it, you could see the kitchen chimney and, beyond that, an opening into the second floor of the house. The hole in the floor had been for a stairway.

Going from the upper floor of the barn all the way down to its basement, we found it still had a dirt floor, along with an exposed field stone and brick foundation.

Devon took one look at the field stone wall and dirt floor, and said, “Here’s where I’m putting my forge.”

This was not a foundation like the ones with which many of us may be familiar. The original builders had actually first constructed a long retaining wall parallel to the road. They then built the house, using part of that wall as the foundation.

The House

By now, we knew the barn could work as a cabinet shop, which was our first consideration. But the question remained: how would we feel about the house itself?

The First Floor

The first floor of the barn connected to the house, leading to a hallway that took us into the kitchen.

Courtesy of Linda Barnes

The kitchen chimney still had an opening for a stove vent, although it was now covered over with paper. Just past it, a stairway went down to the basement of the house. The framing indicated where walls had stood. With all the windows on either side, everything felt spacious and bright. Moreover, much of the framing was not load-bearing, which meant it could be removed to open things up even further.

The original tin ceiling remained, both in the kitchen and the dining room beyond. Prentice and Deb had deliberately left it, hoping the new owners would appreciate it. Aside from the curved wall and that ceiling, there weren’t many other old interior features they could leave in place.

Tin ceilings were first manufactured and sold in North America in the mid 1800s, as a more affordable option to emulate the look and elegance of the ornate plasterwork that was popular in Europe at the time. Tin ceilings were primarily painted white to emulate the plaster ceilings in Europe… The use of tin ceilings really developed in the mid-nineteenth century, when mass produced sheets of thin rolled tin plated steel became readily available in America and reached the zenith of their popularity in the late 1800s to early 1900s.

Brian Greer, “History of Tin Ceilings”

In the dining room, a section had been framed off, the laths that rounded its corner still in place. Devon and I looked at it, and then at each other, and said at almost the same time, “That stays” (just as we had when we saw the tin ceiling, and exactly as Prentice and Deb had hoped).

Turning to the right, we entered the living room, which looked out onto Thompson Street. The front door stood diagonally across the room.

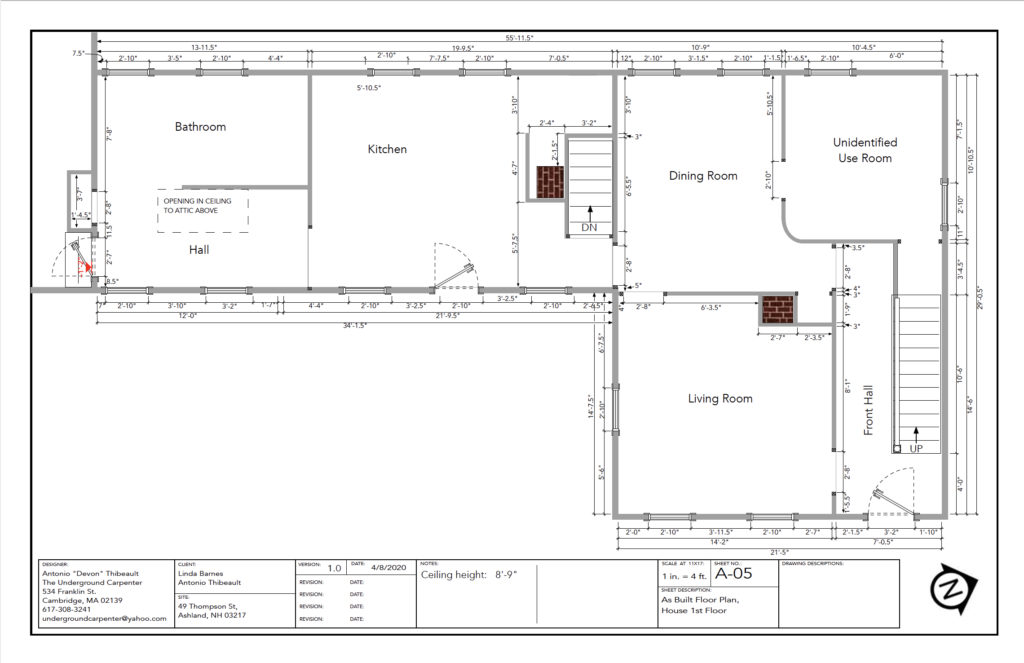

To give you a better idea of how all the parts connect, here is the as-built first-floor plan that Devon later drew. What look like interior walls were actually the sections of bare framing.

The Second Floor

The second floor had consisted of three rooms, with the master bedroom facing the front of the house.

The two other rooms looked out over the back yard. The one to the right was enough smaller that we still wonder whether it had actually been used as a bedroom.

Notice the hole in the wall of the room to the left. It looked through the connector, past the kitchen chimney and the original outer wall of the house and, from there, into the upper floor of the barn.

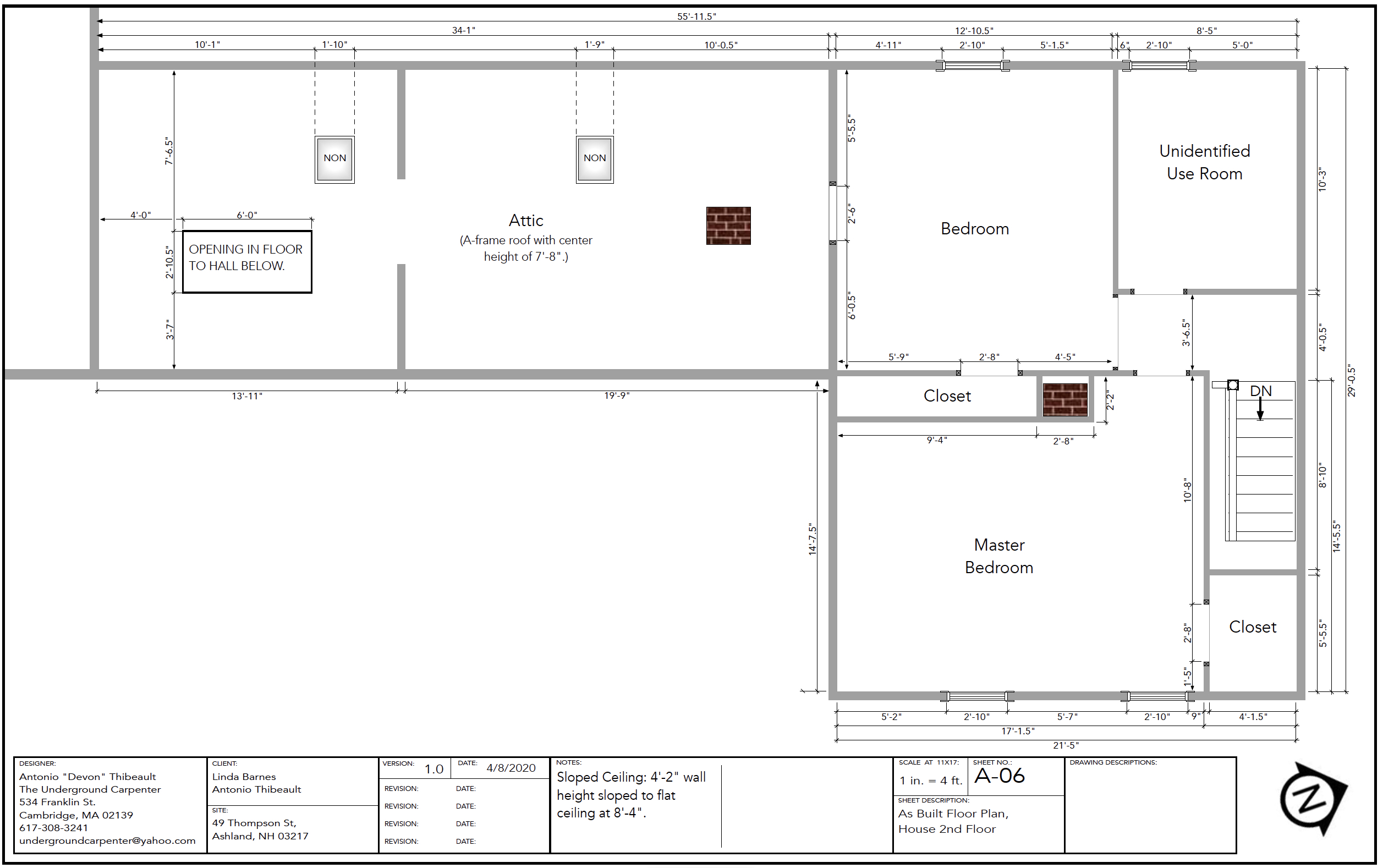

And again, to make it a little easier to visualize the relationships between the parts, here is the as-built plan for the second floor.

The Basement

Finally, there was the basement, which ran the full length of the house. We had not yet seen photographs of its previous condition, and so could not appreciate at the time just how much Prentice and Deb had improved it. Not only had they ripped out the old insulation from the ceiling; Deb had tracked down Robert Guyotte, who poured the cement floor and covered those sections of the stone foundation.

When the cement wall was poured, Deb insisted that the crew leave the holes around the water intake and sewage outtake pipes large enough to accommodate whatever plumbing repairs or new system future owners might have to deal with. She could not have anticipated that Devon and I would, indeed, have to replace the intake pipe. Her foresight spared our having to deal with older pipes locked in concrete. (She later said, “Devon, I didn’t know you then, but I was already thinking of you!”)

The brick column in the foreground (below) was close to collapsing, its mortar crumbled almost half an inch in. Instead of replacing it with something newer, Prentice and Deb repaired the mortar to preserve another original feature of the house.

Decisions

As we left the house, Devon and I whispered to each other, “Let’s make an offer.” So we did. After a few rounds of discussion and to our joy, Prentice accepted.

Because the renovation involved the entire house, securing a mortgage turned into an intensive process of developing a detailed bid in a tightly compressed period of time. We had to arrive at a total projected cost for the undertaking as a whole, which involved each and every facet of the renovation. Think not only new room layouts and floor plans, but also particulars as detailed as choosing and pricing ceiling fans and door knobs.

We could not have done it without the support and expertise of our realtor Jay Polimeno, our longstanding contractor friend, Larry Trombetta, and our mortgage broker Jeff Lundgren. We ate, slept, dreamed, and breathed renovation planning, fretting over each detail we might have left out. At the last minute, we came close to missing our final deadline when we discovered that the bid had to include a subcontractor certified to remove lead paint. (Every house built before 1978 invariably has lead paint.) It was literally the day before everything was due that I finally found someone. But at last it was done and approved.

On December 31, 2019, Devon and I met with Prentice and Deb to sign the closing agreement. As they detailed the work they had done, their love for the house could not have been clearer. We found it difficult to break off the conversation. The notary public had to keep apologetically interrupting the four of us, to bring us back to the task of finalizing the sale.

With the signing done, Prentice and Deb transferred their guardianship of the house to Devon and me. We had become the most recent custodians of the ever emerging statue in the stone.

Acknowledgments

Devon and I would like to extend our deep thanks to Prentice Hammond, Jr. and Debra Hammond for consulting so generously on this post to ensure I had my facts right, and for sharing photographs of the earlier state of the house and of their own work on it. Most of all, we want to thank Prentice for selling the house to us. We also thank Rick Hagan—Prentice’s realtor—and his wife, realtor Linda Hagan, for the use of Linda’s photographs for this page.

Resources

For more detailed explanations of lath and horsehair plaster, check out:

Lipinski, Edward R. 1995. “History is Plastered with Plaster”: https://www.deseret.com/1995/5/14/19175363/history-is-plastered-with-plaster

Bailey, Mike. Horsehair Plaster, “What Is It? What Is It Used For?”: https://www.h2ouse.org/horsehair-plaster/

John Canning & Co., “The History and Use of Horsehair Plaster: https://johncanningco.com/blog/horsehair-plaster/

For a piece on reviving the use of horsehair plaster, take a look at: Inside Out BBC1, “Hairy Lime Plaster -The History”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0yyunMtJsxE

For tips on removing horsehair plaster and lath, a good source is Gary Wentz, “Plaster and Lath Tear-Off Tips”: https://www.familyhandyman.com/list/plaster-and-lath-tear-off-tips/

For more on different approaches to framing barns, see Brice Cochran, “The History of Timber Framing Around the World”: https://timberframehq.com/history-of-timber-framing/

To learn more about the use of tin ceilings, see Brian Greer, “History of Tin Ceilings”: https://www.tinceiling.com/company/history-of-tin-ceilings/

Also Suzanne Spellen (aka Montrose Morris), “America’s Imitation Plaster: Tin Ceilings”: https://www.brownstoner.com/interiors-renovation/tin-ceiling-history-metal-tiles/

Mary Benton

Amazing tale of passion to preserve history, and to pay it forward. Great photos.

Linda Barnes

There are so many other directions a different owner could have taken that would have resulted in the essential death of the house, that we remain moved and impressed by Prentice’s and Deb’s essentially selfless commitment to preserving it.

And on a different note, Devon and I are finding monarch caterpillars chowing down on our milkweed plants. I thought of you every time I saw them working their ways through the large leaves. Most recently, two who got quite pudgy disappeared. I trust that means that they are now off in their cocoons.

Donene

I love this story! And now having had a chance to see the house in person, I’m even more invested in watching this journey. It’s an amazing house, it’s lucky to have you both.

Linda Barnes

We’re thinking of it as the house and its growing circle of friends!

Susan Hammond

So looking forward to seeing the new life of an amazing house. I saw it when it was at it’s worse before Deb and Pren gutted it. But even then you could see it’s potential. They could not have have found better stewards to bring the house to its next chapter.

Linda Barnes

Susan, how nice to meet you through the site! Devon and I are endlessly amazed by the extent to which Prentice and Deb invested their energies and resources, becoming a part of the house’s ongoing story. Acting as stewards is a fine way to characterize our understanding as well!